Archive for the ‘The Existence of God’ Category

Do we have Free Will?

Most naturalists or atheists believe that the mind is totally the result of the physical operation of the brain. If this is true, then all of our thoughts, emotions and choices are due to the physical movements of atoms and molecules within the brain and are ultimately solely due to the laws of physics. It then it seems to strongly imply that all our thoughts and choices are determined by the motion of particles within the brain and that our perception that we have free will is an illusion. (more…)

Should we argue for God’s Existence?

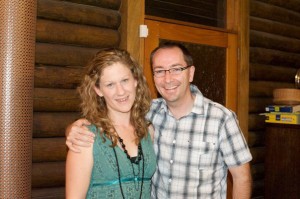

On Thursday the 21st of November Mike Russell spoke on “Should we argue for God’s existence?” Mike believes that we should presuppose God’s existence in apologetic discourse. He calls his apologetic approach ‘no-excuse intuitionism’. The dividing line between what we should argue for using evidence and what we should presuppose is governed by the principle of no excuse. Any element of moral truth that a person needs to know to live a blameless life, he ought to know, and can know by intuition. However, the Holy Spirit works through the arguments and evidences from the Scriptures. Thus any other element of truth that a person needs to know to be saved through Jesus can and should be argued for using evidence and arguments.

So, according to Mike, if you do not believe in God, then you ought to, without requiring any evidence.

Some were convinced and others were not. Mike has provided us with his Power Point Slides and the presentation and discussion has been recorded on You Tube. The full content of his talk is the subject of his current Master’s thesis and so cannot be published. However, he is happy to provide the full text through Reasonable Faith Adelaide, provided that it is not published or passed on. Please email me if you would like a copy. We are also hoping that Mike will provide a brief summary that we can provide with this post.

Mike is married to Ally, and they have four children. He has been a Christian for around 20 years, and is Associate minister at St. George’s Magill. He is currently writing an MTh thesis in the area of apologetics.

Krauss Versus Craig

Why is there something rather than nothing?

Introduction

On Thursday 26th of September, Reasonable Faith Adelaide reviewed the “dialogue” between William Lane Craig and Lawrence Krauss on the topic “Why is there something rather than nothing?” This dialogue was held on the 13th of August in Sydney.

William Lane Craig is the director of Reasonable Faith in the US and is a leading apologetics debater. He spoke at two functions in Adelaide via the City Bible Forum and many of us had the opportunity to hear him and meet him personally. However, his main activity in Australia was the series of “dialogues” with Lawrence Krauss.

Lawrence Krauss is a high profile New Atheist. He has spent a significant time in Australia and has appeared on Q&A on two occasions.

There were 3 dialogues held in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. Krauss chose a dialogue format rather than a debate. This enabled a highly interactive discussion that was quite volatile. For instance, in Brisbane Krauss launched a personal attack on William Lane Craig. He accused him of being a dishonest charlatan. He later softened his line a little and admitted that Craig was a gentleman who sincerely believed in his cause but still accused him of presenting deliberate distortions to bolster his arguments.

I highly recommend that you watch each dialogue and judge for yourself who the honest man really is. They are all now available from the City Bible Forum site at:

http://citybibleforum.org/city/melbourne-brisbane-perth-adelaide-sydney/news/videos-life-universe-and-nothing

The topic “Why is there something rather than nothing?” is closely related to Krauss’ most recent book “A Universe from Nothing”, which was reviewed by Mark Worthing on the 15th of August.

The dialogue format consisted of a 15 minute talk by each speaker followed by a discussion, moderated by Rachael Kohns, the presenter of “The Spirit of Things”, which is an ABC radio show.

Krauss’s Presentation

Krauss spoke first and his main points were:

- Craig presents deliberate distortions

- We are not the centre of the universe. There is no special place.

- We live in flat universe, which has a total energy of zero. This suggests that the universe could come into existence from nothing without any “divine shenanigans”.

- The Bible claimed that the universe had a beginning before science did. However, so did many other creation myths, so what is unique about the Bible? It is often claimed that the Bible is not a scientific book so why suddenly make a switch and claim that Genesis 1:1 is a scientific statement?

- The fine tuning of the laws of physics is a source of fascination. However, a multiverse may explain the fine tuning and the fine tuning could be better. So the fine tuning is not evidence of divine design.

One of Craig’s commonly used arguments is the Kalam Cosmological Argument. He uses this argument to show that the cosmos had a beginning, which requires a transcendent cause by a necessarily existent being. One of the evidences to support a physical beginning is the Borde, Guth and Vlenkin (BGV) Theorem. In response, Krauss’s displayed the following personal email from Vilenkin:

Hi Lawrence,

Any theorem is only as good as its assumptions. The BGV theorem says that if the universe is on average expanding along a given worldline, this worldline cannot be infinite to the past. A possible loophole is that there might be an epoch of contraction prior to the expansion. Models of this sort have been discussed by Aguirre & Gratton and by Carroll & Chen…Jaume Garriga and I are now exploring a picture of the multiverse where the BGV theorem may not apply. In bubbles of negative vacuum energy, expansion is followed by contraction… However, it is conceivable (and many people think likely) that singularities will be resolved in the theory of quantum gravity, so the internal collapse of the bubbles will be followed by an expansion. In this scenario,… it is not at all clear that the BGV assumption (expansion on average) will be satisfied… Of course there is no such thing as absolute certainty in science, especially in matters like the creation of the universe. Note for example that the BGV theorem uses a classical picture of spacetime. In the regime where gravity becomes essentially quantum, we may not even know the right questions to ask.

Alex

Krauss used this email to argue that the BGV theorem did not necessarily indicate a beginning. Krauss reused this email during the Melbourne dialogue. In Melbourne Craig questioned Krauss on the missing bits indicated by the ellipsis markers. Krauss claimed that these were “technical bits”.

Subsequent to the dialogues, Craig wrote to Vilenkin, who supplied the full text of the email, as given below. The sections in bold are the “technical bits” that Krauss omitted.

Hi Lawrence,

Any theorem is only as good as its assumptions. The BGV theorem says that if the universe is on average expanding along a given worldline, this worldline cannot be infinite to the past.

A possible loophole is that there might be an epoch of contraction prior to the expansion. Models of this sort have been discussed by Aguirre & Gratton and by Carroll & Chen. They had to assume though that the minimum of entropy was reached at the bounce and offered no mechanism to enforce this condition. It seems to me that it is essentially equivalent to a beginning.

On the other hand, Jaume Garriga and I are now exploring a picture of the multiverse where the BGV theorem may not apply. In bubbles of negative vacuum energy, expansion is followed by contraction, and it is usually assumed that this ends in a big crunch singularity. However, it is conceivable (and many people think likely) that singularities will be resolved in the theory of quantum gravity, so the internal collapse of the bubbles will be followed by an expansion. In this scenario, a typical worldline will go through a succession of expanding and contracting regions, and it is not at all clear that the BGV assumption (expansion on average) will be satisfied.

I suspect that the theorem can be extended to this case, maybe with some additional assumptions. But of course there is no such thing as absolute certainty in science, especially in matters like the creation of the universe. Note for example that the BGV theorem uses a classical picture of spacetime. In the regime where gravity becomes essentially quantum, we may not even know the right questions to ask.

Alex

The missing bits don’t seem all that technical to me and they do throw a different light on Vilenkin’s views. A more extended record of the discourse between Craig and Vilenkin can be obtained from http://www.reasonablefaith.org/honesty-transparency-full-disclosure-and-bgv-theorem.

If you have been reading this summary carefully, you may have noticed that Krauss’s arguments are not particularly relevant to the topic. However, he did show a short video clip that explained how nothing is more complicated than previously thought. Craig subsequently provided a summary of Krauss’ claims about nothing, which I have listed below.

In 1922, William Hughes Mearns published the following poem.

The other day upon the stair

I met a man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today

Oh, how I wish he’d go away

Mearns is guilty of calling nothing something. However, Krauss seems to be guilty of the opposite sin. He calls something nothing; and this was the main thrust of Craig’s argument.

Craig’s Presentation

“Nothing” is not a different type of something. It is “not anything”. However, Krauss defines something to be nothing. Here are some quotations from Krauss:

- There are a variety of forms of nothing, they all have physical definitions

- The laws of quantum mechanics tell us that nothing is unstable

- 70% of the dominant stuff of the universe is nothing

- There is nothing there, but it has energy

- Nothing weighs something

- Nothing is almost everything

The above quotations were almost identical with Krauss’s video clip. They all illustrate that Krauss is being misleading in his use of the word “nothing”. In all instance his use of nothing is really something, whether it be a quantum vacuum or quantum mechanical systems.

Craig further supported Krauss’s misrepresentation of nothing with a quote from “On the origin of everything” by David Albert, a philosopher of science.

Vacuum states are particular arrangements of elementary physical stuff…the fact that some arrangements of fields happen to correspond to the existence of particles and some don’t is not a whit more mysterious than the fact that some of the possible arrangements of my fingers happen to correspond to the existence of a fist and some don’t. And the fact that particles can pop in and out of existence, over time, as those fields rearrange themselves, is not a whit more mysterious than the fact that fists can pop in and out of existence, over time, as my fingers rearrange themselves. And none of these poppings…amount to anything even remotely in the neighbourhood of a creation from nothing. Krauss is dead wrong and his religious and philosophical critics are absolutely right.

See http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/25/books/review/a-universe-from-nothing-by-lawrence-m-krauss.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 for the full text.

Craig then presented Gottfried Leibniz’ argument for the existence of God based on the Principle of Sufficient Reason:

- Every existing thing has an explanation of its existence (either in the necessity of its own nature or in an external cause).

- If the universe has an explanation of its existence, that explanation is God.

- The universe exists.

- Therefore, the universe has an explanation of its existence (from 1 and 3).

- Therefore, the explanation of the universe’s existence is God (from 2 and 4).

I suggest you watch the video to see how Craig supported this argument.

Discussion

The interesting part of the discussion was on Leibniz’s Cosmological Argument. The central point of discussion was premise 2, “If the universe has an explanation of its existence, that explanation is God.” During Craig’s talk, he had presented arguments to support premise 2. Krauss’s question was, “If there is an explanation, why does it have to be God?” More importantly, what type of explanation are we talking about? Is it a causal explanation or is it about purpose? This is extremely important to the argument and Craig was about to explain. However, at this stage, Rachael (the moderator) was obviously out of her depth and so interrupted the argument with a silly question about aliens. So, all was lost and now we will never know. Thank you Rachael.

Conclusion

Some of the discussion was confusing and difficult to follow. In all 3 dialogues the discussion was hindered by Krauss’s frequent interruptions and shouting over the top of Craig to prevent him from completing his explanations. However, in my opinion one observation was clear from the Sydney dialogue. Krauss is equivocating in his use of nothing. He is confusing something with nothing to argue how the universe could arise from nothing, when it is really something. He has conceded that it is likely that the physical cosmos has a beginning, but has not in reality provided any explanation for its origin or the reason why it exists. Science attempts to explain how the physical world can be transformed from one physical state into another. However, it always presupposes a prior physical state. To explain how the physical world can arise from absolutely nothing is inherently beyond the scope of physics. That is what “meta-physics” is all about.

Kevin Rogers

Kant’s Critique of the Traditional Arguments for the Existence of God

This is a summary of the presentation given on the 4th of July. Unfortunately we were not able to video record the meeting. However, there were power point slides (see Kants Critique).

1 Kant for Dummies

When I was a young engineer, a senior manager at the Electricity Trust told me, “If you really understand something, then you can explain it simply”. I believe this is largely true. So, I am going to attempt to provide a simple explanation of Kant’s Critique of the traditional arguments for the existence of God. Unfortunately the converse does not apply. If you explain something simply, this does not necessarily mean that you really understand. Anyway, here we go.

After reading Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, the German Lutheran Pietist J. G. Hamann wrote “If it is fools who say in their heart there is no God, those who try to prove his existence seem to me to be even more foolish.” However, are Kant’s arguments correct and was Hamann right in his assessment? In fact, Kant’s arguments have not been universally accepted. So, at the risk of being a fool, I will reconsider Kant’s arguments and assess whether it is sound and valid to argue for the existence of God.

So, what were his arguments, are they valid, are they relevant to contemporary arguments and how do they affect the scope and usefulness of arguments for the existence of God?

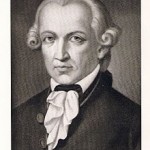

1.1 Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) was a major philosopher during the period of the Enlightenment, which is a supposedly anti-Christian movement. However, Kant is not necessarily anti-Christian. He was brought up in a devout Lutheran family and never rejected that faith. Although he is famous for having launched a critique against the traditional arguments for the existence of God, he still believed in God. In fact he believed that atheism was dangerous to society and also developed an argument for the existence of God based on morality as outlined in his Critique of Practical Reason. Thus we can consider Kant’s critique as “friendly fire”. His intent was to clarify the limitations of the traditional arguments so that their claims were not overstated.

During the Enlightenment the 2 major epistemological movements were rationalism and empiricism. The chief originator of empiricism was John Locke, who believed that all of our knowledge came through the senses. Rene Descartes was the father of rationalism. Descartes’ aim was to gain certain knowledge from a foundation of indubitable beliefs and to derive certain conclusions from that foundation using “Pure Reason”.

1.2 Critique of Pure Reason

Kant’s major work was the Critique of Pure Reason (1787). Kant was primarily an empiricist and his critique was an attempt to unite empiricism with rationalism, which he referred to as Pure Reason. In this work Kant also provided a critique of the traditional arguments for the existence of God. Kant’s critique has been highly influential.

Kant’s analysis of the arguments for the existence of God are contained in Transcendental Doctrine of Elements, Second Part, Second Division, Book 2, chapter 3, sections 3 to 7 of the Critique of Pure Reason.

2 Definitions of Terms

Before we review the traditional arguments we should be careful to define out terms, especially regarding existence. At least 3 types of existence have been identified. These are:

- Impossible existence

- Contingent existence and

- Necessary existence.

Impossible existence refers to entities that cannot exist. These are usually entities that are logically impossible, such as square circles and married bachelors.

Contingent objects are those that we typically observe. They have a beginning, they are caused and we can imagine a world in which they do not exist. In other words they do not have to exist.

When we talk about God it is generally assumed that God is a Necessary Being. This may come in a number of flavours. It may mean that he is uncaused or has no beginning and is the cause of all other things. However, there is an even stronger sense. It may also mean that he exists necessarily. In other words it is impossible for God not to exist and that he must exist in all possible worlds. However, when we say that God is eternal and uncaused, are we necessarily asserting that God is necessary in this last and strongest sense?

Let us keep this in mind as we review Kant’s objections.

3 The Traditional Arguments for Existence of God

According to Kant (1787), there are only 3 arguments that need be considered. These are the Teleological (Design), Cosmological (First Cause) and Ontological arguments. “More there are not, and more there cannot be.” Why is this so? He does not say, but let’s just see what he says.

The Cosmological and Teleological arguments have been around since Plato and Aristotle. They depend on observations about the actual world and even have some basis in scripture, since Paul claims that God’s eternal power and divine nature is clearly perceived in what he has made.

The Ontological Argument, however, is of a quite different nature. It was invented much later in the 11th century. Nobody had thought of it before. It is nearly a purely logical argument with no reference to any particular thing in the actual world, except perhaps our minds.

Although the Cosmological and Design Arguments are much older than the Ontological Argument, Kant considers the Ontological Argument first. He argues that the Ontological Argument is a poor argument. He then argues that the other 2 arguments are ultimately dependent on the Ontological Argument and thus fall with it.

Thus firstly we will consider the Ontological Argument.

4 Ontological Argument

We have already considered the Ontological Argument 4 weeks ago (see https://reasonablefaithadelaide.org.au/the-ontological-argument/). However, I will give an overview. This will be an introduction for those who were not present at that meeting and some revision for those who were. I will provide an overview of the historical development of the Ontological Argument prior to Kant. This will cover Anselm, Gaunilo and Descartes. I will then summarise Kant’s Objections to the Ontological Argument, then compare modern Ontological Arguments and then give assessment of the relevance of Kant’s critique.

4.1 Anselm

The Ontological Argument was first developed by a Benedictine monk called Anselm (1033-1109), who later became Archbishop of Canterbury. The Ontological Argument is contained in the Proslogion, which means “discourse on the existence of God”. Even if his argument is not correct, it really is a stunning piece of original thinking.

Psalm 14 states that “The fool says in his heart ‘There is no God’”. Anselm alludes to this passage and argues that even a fool has a concept of God. He states,

Hence, even the fool is convinced that something exists in the understanding, at least, than which nothing greater can be conceived. For, when he hears of this, he understands it. And whatever is understood, exists in the understanding. And assuredly that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone. For, suppose it exists in the understanding alone: then it can be conceived to exist in reality; which is greater. Therefore, if that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, exists in the understanding alone, the very being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, is one, than which a greater can be conceived. But obviously this is impossible. Hence, there is no doubt that there exists a being than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality.

This passage is quite verbose, but we can simplify it a bit. Anselm reasoned that, if “that than which nothing greater can be conceived” existed only in the intellect, then it would not be “that than which nothing greater can be conceived”, since it can be thought to exist in reality, which is greater. Thus it follows that “that than which nothing greater can be conceived” must exist in reality.

Alvin Plantinga has provided a summary of Anselm’s argument in a more logical form:

- God is defined as the greatest conceivable being

- To exist is greater than to not exist

- If God does not exist then we can conceive of a greater being that does exist

- Thus if God does not exist then he is not the greatest conceivable being

- This leads to a contradiction

- Therefore God must exist

4.2 Gaunilo of Marmoutiers

In Anselm’s own time, his argument was opposed by Gaunilo of Marmoutiers. He parodied the argument by applying it to other entities, such as “A greatest conceivable island” or “a greatest conceivable lion”. This tactic has often been used to parody the ontological argument. However, this was not the approach taken by Immanuel Kant.

4.3 Descartes

The Ontological Argument was developed further by philosophers such as Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz.

Descartes’ simplified argument can be summarised as:

- The very conception of God includes the possession of all perfections.

- Existence is a perfection.

- Therefore, it is inconceivable that God does not exist.

4.4 Kant’s Ontological Argument Objections

It is difficult to summarise Kant’s critique of the Ontological Argument simply. However, it seems that Kant is mainly targeting Descartes’ version, although he does not make this clear. The major points that he seems to be raising are.

- The Ontological Argument confuses existence and essence

- Existence is not a Predicate

- Negation of the proposition “God exists” does not result in a contradiction

- You cannot establish God’s existence merely from our conceptions of God

Kant’s critique of the Ontological Argument has not gone unchallenged. For each of Kant’s objections, I will mention counter objections that have been raised.

4.4.1 Confusing Existence and Essence

Descartes’ version of the Ontological Argument can be summarised as

- The very conception of God includes the possession of all perfections.

- Existence is a perfection.

- Therefore, it is inconceivable that God does not exist.

Descartes claims that existence is a perfection. However, Kant believes that Decartes is confusing essence with existence. The essence of God answers the question, “What is God like?” and describes God’s properties or characteristics, such as omniscience. However, the existence of God answers the question, “Does God exist?” Essence and existence are 2 different things. When Descartes claims that existence is a perfection, he is confusing or conflating essence with existence. On this issue Kant may well be right.

4.4.2 Existence is Not a Predicate

Kant’s main critique of Anselm’s and Descartes’ version of the Ontological Argument is that existence is not a predicate. Propositions consist of a subject and a predicate. For instance, in the sentence “A dog has four legs”, the dog is the subject and “has four legs” is the predicate. The predicate describes properties of the subject. By claiming that existence is not a predicate, Kant is challenging the claim that existence is a perfection, or that to exist is greater than to not exist.

4.4.3 Negation is not a Contradiction

Kant claims that “God exists” is not a necessary truth. Some statements are necessarily true, since their negation entails a contradiction. A couple of examples are:

- All bachelors are unmarried

- All squares have 4 sides

If we negate the predicate we get a contradiction, eg

- All bachelors are married

- All squares do not have 4 sides

However, consider the statement “God exists”. If we negate the predicate we get “God does not exist”. However “God does not exist” is a coherent statement that does not entail a contradiction. Thus Kant argues that “God exists” is not a necessary truth. In this respect I think Kant is right. The statement “God exists” is not a necessary truth. However, I think Kant confuses “necessary truth” with “Necessary Being”. The Ontological Argument is not arguing that “God exists” is a necessary truth. It is arguing that God exists necessarily, and that is different.

4.4.4 Conceptual Conundrum

Anselm argues for concepts in our minds to the objective existence of God. However, Kant argues that we cannot establish God’s existence merely from our conceptions of God. How can a conceptual conundrum in the mind affect a being’s objective existence?

4.4.5 Kant’s Conclusion

Thus Kant concludes his discussion with the cutting assessment that the Ontological Argument “neither satisfies the healthy common sense of humanity, nor sustains the scientific examination of the philosopher.”

This all sounds very damning, but are Kant’s objections valid?

Kant claims that he is targeting Ontological arguments in general, but he seems to be mainly targeting Descartes’ version rather than Anselm’s.

4.5 Response to Kant’s Ontological Argument Objections

Two objections to Kant’s critique of the Ontological Argument are that

- His Predicate Argument is irrelevant, and that

- Necessary Existence is indeed a Property

4.5.1 Predicate Argument is Irrelevant

Kant’s most famous objection to the Ontological Argument is his claim that existence is not a predicate. However, even this has been challenged by eminent philosophers. Alvin Plantinga has claimed that Kant’s predicate argument is irrelevant to Anselm’s Ontological Argument.

He states:

Kant’s point, then, is that one cannot define things into existence because existence is not a real property or predicate in the explained sense. If this is what he means, he’s certainly right. But is it relevant to the ontological argument? Couldn’t Anselm thank Kant for this interesting point and proceed merrily on his way? Where did he try to define God into being by adding existence to a list of properties that defined some concept? …If this were Anselm’s procedure … then indeed his argument would be subject to the Kantian criticism. But he didn’t, and it isn’t. The usual criticisms of Anselm’s argument, then, leave much to be desired. Of course, this doesn’t mean that the argument is successful, but it does mean that we shall have to take an independent look at it.

Plantinga’s counter objections are not universally accepted (Robson 2012). However, they do illustrate that Kant’s predicate critique of Anselm’s version of the Ontological Argument is not universally considered to be watertight.

4.5.2 Necessary Existence is a Property

One of Kant’s key claims is that existence is not a property and the Ontological Argument fails because it assumes it is. However, he then proceeds to apply this to necessary existence. The idea of necessary existence is not the same thing as the idea of a being whose properties include existence. A being exists necessarily if it is impossible for that being not to exist. This need not involve the inclusion of a property called existence. Necessary existence is a type of existence and hence necessary existence is indeed a property.

4.6 Does it apply to Modern Arguments?

Alvin Plantinga has been critical of Kant’s arguments regarding Anselm’s formulation of the Ontological Argument. However, he has also proposed a revised form of the ontological argument called the Modal Ontological Argument, which goes as follows:

- It is possible that a Maximally Great Being exists

- If it is possible that a Maximally Great Being exists, then a Maximally Great Being exists in some possible world

- If a Maximally Great Being exists in some possible world, then a Maximally Great Being exists in every possible world

- If a Maximally Great Being exists in every possible world then a Maximally Great Being exists in the actual world

- Therefore a Maximally Great Being exists

Plantinga believes that his argument avoids Kant’s fire. He claims:

Now we no longer need the supposition that necessary existence is a perfection; for obviously a being can’t be omnipotent (or for that matter omniscient or morally perfect) in a given world unless it exists in that world… It follows that there actually exists a being that is omnipotent, omniscient, and morally perfect; this being, furthermore, exists and has these qualities in every other world as well.

However, Plantinga concedes:

But obviously this isn’t a proof; no one who didn’t already accept the conclusion, would accept the first premise. The ontological argument we’ve been examining isn’t just like this one, of course, but it must be conceded that not everyone who understands and reflects on its central premise — that the existence of a maximally great being is possible — will accept it. Still, it is evident, I think, that there is nothing contrary to reason or irrational in accepting this premise. What I claim for this argument, therefore, is that it establishes, not the truth of theism, but its rational acceptability. And hence it accomplishes at least one of the aims of the tradition of natural theology.

4.7 The Essence of the Ontological Argument

To me the essence of the Ontological Argument is that if it is possible that a Necessary Being exists, then a Necessary Being must exist in all possible worlds. This seems quite logical. However, the following issues still need to be resolved:

- Is a Necessary Being possible?

- Can we show that the Necessary Being is maximally perfect and is God?

4.8 Conclusion on the Ontological Argument

There seems to be an essential difference between Anselm’s version of the Ontological Argument and Plantinga’s. Anselm seems to be arguing that it is impossible for God not to exist, whereas Plantinga is arguing that if it is possible for God to exist, then he must exist. However, he leaves the possibility of God’s existence as an open issue that people will debate. Thus Plantinga concludes that it is rational to believe in God but the Modal Ontological Argument is not a proof.

Personally I am not convinced by either Anselm’s or Decartes’ version of the Ontological Argument and so I am not overly perturbed by Kant’s critique. However, I am more interested in his critique of the Cosmological argument. Has Kant undermined the Cosmological Argument in all of its possible forms?

At first sight it seems strange that Kant can possibly claim that the Cosmological Argument and Design Argument are dependent on the Ontological Argument. After all the Cosmological Argument and Design Argument have been around for over a thousand years before the Ontological Argument was ever thought of (or conceived – pun intended).

However, Kant believes that the cosmological and design proofs presuppose the ontological proof since these proofs conclude that a Necessary Being must be a most real or most excellent being. Thus even if the Cosmological Argument or Design Argument can show that a Necessary Being must exist, they then rely on the Ontological Argument to show that the Necessary Being is God.

Kant then argued that the Cosmological Argument is dependent on the Ontological Argument. Thus he believes that, if the Ontological Argument fails, the Cosmological Argument and the Design Argument fall with it.

Firstly we will consider the Cosmological Argument.

5 Cosmological Argument

Kant’s main attack on the Cosmological Argument is that it is dependent on the Ontological Argument. The Ontological Argument argues God is a Necessary Being. Kant claims that the Cosmological Argument argues for the existence of a Necessary Being, which it then identifies as God. Kant accepts that there must be a Necessary Being in order to avoid an infinite regress. However, he disputes that it can be proven that the Necessary Being is God. He believes that the Cosmological Argument relies on the Ontological Argument to make that association. Thus if the Ontological Argument fails then the Cosmological Argument falls with it. However, is Kant right about this dependency?

5.1 Dependency Arguments

Kant seems to use 3 arguments to show the dependency of the Cosmological Argument on the Ontological Argument.

Kant’s key arguments for making the Cosmological Argument dependent on the Ontological Argument are that the Cosmological Argument assumes that:

- a Necessary Being is Possible

- the Necessary Being is Actual

- the Necessary is God

5.1.1 Necessary Existence is Possible

Firstly the Cosmological Argument seems to presuppose that necessary existence is possible and then shows that it is actual, since if it is not possible then it cannot be actual. Kant’s argument goes something like this:

- The concept of a Necessary Being appears in both arguments.

- The Cosmological Argument assumes that necessary existence is at least possible since if it is not possible it cannot be actual.

- This is a conclusion of the Ontological Argument.

- Thus the Cosmological Argument is dependent on the Ontological Argument.

However, the Cosmological Argument does not assume that necessary existence is possible. Instead, the argument tries to show that necessary existence is actual, from which we can infer that it must be possible. This practice is currently used in science. Cosmologists have proposed the existence of Dark Matter and Dark Energy to explain the motion of galaxies. They have little idea what they are and so cannot directly prove that they are possible. However since they are actual, they must be possible.

5.1.2 The Necessary Being is God

The second reason that Kant provides for the dependency of the Cosmological Argument on the Ontological Argument is that the Cosmological Argument relies on the Ontological Argument to associate the Necessary Being with God. Kant claims that the Ontological Argument shows that God is a Necessary Being and therefore exists. The Cosmological Argument shows that a Necessary Being exists, but then relies on the Ontological Argument to infer that the Necessary Being is God.

However, this is not necessarily so. William Lane Craig’s Kalam Cosmological Argument does not go via this route. We will discuss the Kalam Cosmological Argument later.

5.2 Additional Objections

As well as claiming that the Cosmological Argument is dependent on the Ontological Argument, Kant raises additional objections to the Cosmological Argument itself.

Kant thinks that space and time are absolutely necessary and are examples of some things that are necessarily existent apart from God. However, Kant’s views are simply dated and have been overtaken by recent scientific discoveries.

One of Kant’s aims was to define appropriate limits for the exercise of pure reason. He does not disparage pure reason altogether as much of his critique is pure reason. However, his belief that space and time were infinite and existed independently of God was, he believed, a valid conclusion based on pure reason. It was this belief that caused him to claim that a finite past led to contradictions. However, it appears he was wrong. Later empirical evidence has led to the conclusion that space and time are finite, which means that there is no contradiction if the universe has a finite past. In this case, it seems that Kant has overstepped the use of pure reason, which probably illustrates his point.

5.3 Kalam Cosmological Argument

William Lane Craig is a current proponent of the Kalam Cosmological Argument.

I will cover:

- The argument

- Justifying the premises

- The conclusions drawn

5.3.1 The Argument

Craig’s formulation of the Kalam Cosmological Argument can be summarised by the following syllogism (2008):

- Everything that begins to exist has a cause.

- The universe began to exist.

- Therefore the universe has a cause.

5.3.2 Justifying the Premises

For the most part, premise 1 is usually accepted as being intuitively obvious. Most of his effort goes into justifying premise 2. Premise 2 is justified using 2 philosophical arguments and 2 arguments from scientific discoveries during the last 100 years, which are:

- Philosophical Arguments

- It is impossible to instantiate an actually infinite set. Thus there cannot be an infinite sequence of causes.

- It is impossible to traverse an infinite sequence of causes.

- Scientific Arguments

- The second law of thermodynamics implies that there cannot be an infinite past.

- The expansion of the universe implies that the universe cannot be past infinite and originated in an event 13.3 billion years ago, referred to as the Big Bang.

5.3.3 Argument Conclusions

Craig then uses information about the Big Bang to derive various attributes of the initial cause. The Big Bang marked the beginning of matter, energy, space and time. Thus the cause must at least be transcendent, timeless and powerful. These attributes are not derived from any a priori argument.

The Kalam Cosmological Argument does not argue that the cause of the universe is a Necessary Being or even God. It limits itself to those properties that are directly implied by the empirical and logical evidence.

6 Design Argument

Kant (1787) says that the Design Argument may demonstrate a designer who modifies the form of matter but not a creator of matter. To demonstrate the existence of a creator, we must rely on the Ontological Argument and the Cosmological Argument, which he regards as spurious. This proof can at most, therefore, demonstrate the existence of an architect of the world, whose efforts are limited by the capabilities of the material with which he works, but not of a creator of the world, to whom all things are subject.

In other words, the Design Argument may still be valid, but it is just limited in scope. However, this is not of serious concern. The aim of the arguments for the existence of God is mainly to establish God’s existence, not to completely define God’s attributes, and if the Design Argument is sound, then it is also decisive. The main challenge to the Design argument came much later with Darwin’s theory of evolution, which provided a naturalistic explanation of design within living creatures. To overcome this, the Design Argument has been revived in the form of the Fine Tuning Argument, which highlights design in the laws of physics, which are not subject to a Darwinian explanation. Craig’s formulation of the Fine Tuning Argument can be summarised by the following syllogism:

- The fine tuning of the initial conditions of the universe and of the constants in the laws of physics are due to law, chance or design.

- They are not due to law or chance.

- Therefore they are due to design.

Craig then uses this syllogism to argue for a designer of the universe.

7 Craig’s arguments

From all of the above arguments it is deduced that God is maximally great, exists necessarily, is transcendent, timeless, powerful and the designer of the universe. The Plantinga version of the Ontological argument is not subject to the critique that existence is a perfection. The Kalam Cosmological Argument and the Fine Tuning Argument do not rely on any support from the Ontological Argument. Thus these arguments are immune from the main thrust of Kant’s critiques. However, these arguments still have limitations. They are arguments, not proofs. An atheist can always choose not to believe the premises, although the intent is to make the atheist pay an intellectual price for doing so. If well presented, they should demonstrate that it is rational and reasonable to believe in God. In addition, these arguments do not specifically point to the Christian God and are used by Jews and Muslims as well. Specifically Christian arguments must rely on evidence from the New Testament.

I personally do not find the Ontological Argument to be particularly compelling, but I do find the Kalam Cosmological Argument and the Fine Tuning Argument to be quite convincing. I believe this has Biblical warrant, “For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities – his eternal power and divine nature – have been clearly seen, being understood from what he has made, so that men are without excuse” (Romans 1:20). Here Paul seems to be agreeing with the main thrust of the Cosmological and Design Arguments by saying that the observable world provides compelling evidences for some of the properties of the invisible God. If Paul is correct, then well-constructed Cosmological and Design Arguments should provide reasonable evidence for the existence of God.

8 Conclusion on Validity

Kant was also a man of his own time. He lived during the peak of the Enlightenment and many of his views reflect that influence. For instance, Kant claims that the Cosmological Argument is based on the “spurious transcendental law of causality”. It is not certain whether Kant is deriding the law of causality in general or just the notion of a transcendent cause. However, this statement reflects Hume’s scepticism regarding cause and effect, but should we concur with Kant that the principle of cause and effect is spurious? The Enlightenment project aimed to achieve certainty either by rationalism or empiricism. However, it failed to provide assurance even on the principle of cause and effect. However, this principle is the basis of science and is intuitively accepted to be true. After all, according to Francis Bacon, “science is the study of secondary causes”. Kant’s scepticism should be borne in mind when evaluating his critique of the Cosmological Argument. Kant is working from a standard of rigour and a desire for certainty that most scientists and ordinary people would consider to be unrealistic.

There have been a number of critics that have shown that there are numerous weaknesses in Kant’s arguments. However, his arguments have still been widely accepted, even amongst Christian theologians and apologists. Why is this so? Joyce (1922) provides a possible explanation:

It is not to be denied that ever since Kant’s time an impression has prevailed widely that the old proofs are no longer defensible. Possibly the mere fact that an eminent thinker had ventured to call in question such seemingly irrefutable arguments seemed by itself almost equivalent to a disproof. But another reason also, extrinsic it is true to the merits of the criticism, but none the less effective, operated in favour of this result. During the last century, rationalism, in the form either of naturalism or of idealism, had become strongly entrenched in the great centres of learning. It was only natural that thinkers who had discarded belief in a personal God should applaud Kant’s conclusion, even if they might hesitate to affirm that his criticism of the proofs was in all respects sound. Thus it came about that those who admitted the value of the traditional arguments were regarded as out of date. Often the validity of Kant’s objections is simply taken for granted, and the proofs of God’s existence dismissed without more ado. Even some of the apologists of revealed religion, eager not to be behind the fashion, discard them as untenable.

9 Assessment

Probably the strongest point that Kant made was that existence is not a predicate, which (to some degree) undermined the Ontological Argument, as formulated by Anselm and simplified by Descartes. Prior to Kant the arguments were regarded as proofs. One of the themes that came out of the Enlightenment was that this level of certainty is just not possible. On the other hand, I believe that Kant’s arguments on the dependency of the Cosmological Argument and Design arguments on the Ontological Argument are highly dubious.

I believe it is beneficial to be aware of Kant’s arguments and to be careful not to overstate the effectiveness and scope of Craig’s arguments. They are arguments, not proofs. However, people like Craig and Plantinga are well aware of Kant’s critique and their arguments are well crafted to avoid Kant’s fire. I have not seen any debate where Craig has been attacked directly on the basis of Kant’s critique, but occasionally some of Kant’s arguments do reappear without Kant being directly invoked.

Thus, in conclusion, I believe we can thank Kant for his interesting points and then proceed merrily on our way.

10 References

Craig, W.L. Reasonable Faith: Christian Truth and Apologetics, 3rd edition, Crossway, Wheaton, Illinois, 2008.

Joyce, G.H., Principles of Natural Theology, Longmans, Green and Co., New York, Toronto, Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, 1922.

Kant, I. The Critique of Pure Reason, 2nd edition, 1787, translated by J.M.D. Meiklejohn, A Penn State Electronic Classic Series Publication, Pennsylvania State University, 2010.

Koons, R.C. Western Theism, Lecture notes and bibliography from Dr. Koons’ Western Theism course (Phl 356) at the University of Texas at Austin, Spring 1998, http://www.leaderu.com/offices/koons/, in particular Lectures 5&9.

Plantinga, Alvin, God, Freedom and Evil, New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1974. The pertinent section on the ontological argument is quoted at http://mind.ucsd.edu/syllabi/02-03/01w/readings/plantinga.html.

Robson, Gregory, The Ontological Proof: Kant’s Objections, Plantinga’s Reply, KSO 2012: 122-171, posted August 26, 2012 www.kantstudiesonline.net.

Worthing, M., Apologetics Intensive Lecture Notes, Section 05, Apologetics, proofs and science, 2012.

http://www.scandalon.co.uk/philosophy/philosophy.htm

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cosmological-argument/

http://www3.nd.edu/Departments/Maritain/etext/pnt.htm

The Ontological Argument

On Thursday the 6th of June we discussed the Ontological argument. The Ontological Argument (OA) is an argument for the existence of God based on reason alone without virtually any reference to scientific or historical evidence. The purpose of our discussion was to familiarise ourselves with the argument and the issues that surround it rather than to argue vehemently for its truth. The meeting was recorded via the Video Recording and the Power Point Slides.

The content of the presentation is also summarised as follows:

1 Introduction

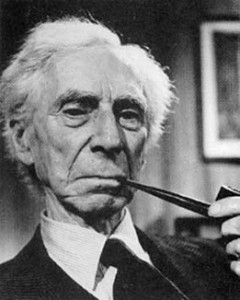

The Ontological Argument has been highly controversial and maligned ever since it was first conceived. For instance, the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer described the OA as a “sleight of hand trick” or “a charming joke”. Bertrand Russell was also dismissive, but with some reservations. He stated,

It is much easier to be persuaded that ontological arguments are no good than it is to say exactly what is wrong with them.

The OA appears at first to be absurd, until you really start to think about it. Alvin Pantinga puts it this way,

Although the [ontological] argument certainly looks at first sight as if it ought to be unsound, it is profoundly difficult to say what, exactly, is wrong with it. Indeed, I do not believe that any philosopher has ever given a cogent and conclusive refutation of the ontological argument in its various forms.

Other common arguments for the existence of God are the Cosmological and Design Arguments. These rely on observations about the actual world. They both precede the OA by over a thousand years since they have their origins in the writings of Plato and Aristotle. One can even find justification for these arguments in the writings of the apostle Paul in Romans 1. However, the OA is radically different. It is an argument based upon what Immanuel Kant calls, “Pure Reason”. It is a purely logical argument that has virtually no reference to the actual world.

2 Anselm of Canterbury

The OA was first conceived rather late in history by a Monk in the 11th Century. Saint Anselm of Canterbury (c.?1033 – 21 April 1109) was a Benedictine monk, who held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to 1109. He has been a major influence in Western theology. Anselm sought to understand Christian doctrine through reason and develop intelligible truths interwoven with the Christian belief. He believed that the necessary preliminary for this was possession of the Christian faith. He wrote, “Nor do I seek to understand that I may believe, but I believe that I may understand. For this, too, I believe, that, unless I first believe, I shall not understand.” In his Proslogion (which means Discourse on the Existence of God), Anselm put forward a “proof” of the existence of God which was later called the “ontological argument”. The term itself was first applied by Immanuel Kant to the arguments of Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century rationalists (Descartes and Leibniz). Anselm defined his belief in the existence of God using the phrase “that than which nothing greater can be conceived”.

In the Psalms it says “The fool says in his heart, ‘There is no God’”. Thus Anselm argues that even the fool has a concept of God. A critical passage from the Proslogion is as follows:

Hence, even the fool is convinced that something exists in the understanding, at least, than which nothing greater can be conceived. For, when he hears of this, he understands it. And whatever is understood, exists in the understanding. And assuredly that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone. For, suppose it exists in the understanding alone: then it can be conceived to exist in reality; which is greater. Therefore, if that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, exists in the understanding alone, the very being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, is one than which a greater can be conceived. But obviously this is impossible. Hence, there is no doubt that there exists a being than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality.

This passage is quite verbose, but we can simplify it a bit. He reasoned that, if “that than which nothing greater can be conceived” existed only in the intellect, then it would not be “that than which nothing greater can be conceived”, since it can be thought to exist in reality, which is greater. It follows, according to Anselm, that “that than which nothing greater can be conceived” must exist in reality. The bulk of the Proslogion is taken up with Anselm’s attempt to establish the identity of “that than which nothing greater can be conceived” as God, and thus to establish that God exists in reality. Anselm wrote in an informal style before the days of philosophical precision. However, Alvin Plantinga has provided a formalised rewording of Anselm’s Argument.

- God is defined as the greatest conceivable being

- To exist is greater than to not exist

- If God does not exist then we can conceive of a greater being that does exist

- Thus if God does not exist then he is not the greatest conceivable being

- This leads to a contradiction

- Therefore God must exist

3 Gaunilo

Anselm’s ontological proof has been the subject of controversy since it was first published in the 1070s. It was opposed at the time by a fellow 11th century Benedictine monk called Gaunilo of Marmoutiers. He argued that humans cannot pass from intellect to reality. In Behalf of the Fool, Gaunilo refutes Anselm using a parody of Anselm’s argument

- The Lost Island is that than which no greater can be conceived

- It is greater to exist in reality than merely as an idea

- If the Lost Island does not exist, one can conceive of an even greater island, i.e., one that does exist

- Therefore, the Lost Island exists in reality

Most attacks on the OA are based on parodies. If the same argument can be used to prove something absurd, then there must be something wrong with the original argument. This process is valid. However, usually there is something wrong with the parody. In Gaunilo’s case there is No intrinsic maximum for the greatest conceivable island. How many palm trees and dancing girls constitute the greatest conceivable island? Thus “a greatest conceivable island” is not a coherent concept? Gaunilo’s criticism is repeated by several later philosophers, among whom are Thomas Aquinas and Kant. In fact much of the criticism has come from people who already believed in God.

4 The Rationalists

Rene Descartes is an extremely important person in the development of Western Philosophy. He is considered the father of modern philosophy and the father of rationalism as well as being a great mathematician. Rationalism was a movement that aimed to obtain certain knowledge by pure reason alone. Anyway he contributed to the development of the OA. He introduced the idea that existence is a perfection. He also introduced an intuitive argument for the existence of God. The more you ponder the nature of God, the more it becomes evident to the intuition that God must exist. Descartes’ argument can be summarised as follows: • God is a supremely perfect being, holding all perfections

- Existence is a perfection

- It would be more perfect to exist than not to exist

- If the notion of God did not include existence, it would not be supremely perfect, as it would be lacking a perfection

- Consequently, the notion of a supremely perfect God who does not exist is unintelligible

- Therefore, according to his nature, God must exist

Leibniz was also a Rationalist. He extended Descartes’ argument because he knew that Descartes’ argument fails unless one can show:

- That the idea of a supremely perfect being is coherent, or

- That it is possible for there to be a supremely perfect being.

He claimed that it is impossible to demonstrate that perfections are incompatible and thus all perfections can co-exist together in a single entity. Since he considered logic associated with necessity and possibility was in fact a forerunner of modal logic and the Modal Ontological Argument.

5 Kant’s Critique

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) was an Enlightenment Philosopher. His greatest work was the Critique of Pure Reason in which he attempted to unite empiricism and rationalism (Pure Reason). Within the Critique of Pure Reason he launched what many consider a devastating critique of the traditional arguments for existence of God, in particular

- The Ontological argument,

- The Cosmological argument, and

- The Teleological (or Design) argument.

This doesn’t mean he was an atheist. In fact he believed in God, but this belief was based on the moral argument. Hence we can consider his arguments as friendly fire. Kant launched at least 3 criticisms of the OA. They are:

- Existence is not a predicate

- How can a conceptual conundrum in the mind affect a being’s objective existence?

- Negation does not entail a contradiction

We will look at each of these criticisms.

5.1 Existence is not a predicate

Kant is famous for his claim that existence is not a predicate. However, what is a predicate? The definition of the meaning of predicate is crucial to Kant’s argument. One way of defining predicate is to say that all propositions consist of a subject and a predicate. For example, consider the statement, “A dog has 4 legs”. “A dog” is the subject and “has 4 legs” is the predicate. That seems to make sense. However, consider the proposition “God exists”. God is the subject and exists is the predicate. Thus existence is a predicate and so Kant must be wrong. However, Kant is not that stupid. Predicate can be defined in other ways. The predicate contains the properties of the subject. Kant argued that existence is an instantiation of an object and thus existence is not a property, nor is it a perfection. Kant was not so much undermining Anselm’s version of the OA. He was primarily aiming at Descartes’ version of the argument as Descartes had claimed that existence is a perfection and thus it would be more perfect to exist than not to exist.

5.2 Conceptual Conundrum

Anselm argues for concepts in our minds to the objective existence of God. However, how can a conceptual conundrum in the mind affect a being’s objective existence? It makes me wonder.

5.3 Negation is not a Contradiction

Some statements are necessarily true, since their negation entails a contradiction. Examples of statements that are necessarily true are:

- All bachelors are unmarried

- All squares have 4 sides

However “God does not exist” is a coherent statement that does not entail a contradiction. Thus Kant argues that “God exists” is not a necessary truth. In this respect I think Kant is right. The statement “God exists” is not a necessary truth. However, I think Kant confuses “necessary truth” with “necessary being”.

Thus Kant concludes that the Ontological Argument “neither satisfies the healthy common sense of humanity, nor sustains the scientific examination of the philosopher.” However, Kant’s views are not universally accepted. We are going to look at Plantinga’s Modal Ontological Argument but firstly we will look at what Plantinga has to say about Kant, in particular his predicate argument. Plantinga says:

Kant’s point, then, is that one cannot define things into existence because existence is not a real property or predicate in the explained sense. If this is what he means, he’s certainly right. But is it relevant to the ontological argument? Couldn’t Anselm thank Kant for this interesting point and proceed merrily on his way? Where did he try to define God into being by adding existence to a list of properties that defined some concept? If this were Anselm’s procedure — if he had simply added existence to a concept that has application contingently if at all — then indeed his argument would be subject to the Kantian criticism. But he didn’t, and it isn’t. The usual criticisms of Anselm’s argument, then, leave much to be desired.

Plantinga may or may not be right. The point is that Kant’s views are not universally accepted.

6 The Modal Ontological Argument

Alvin Plantinga has produced a version of the Ontological Argument that is based on modal logic and is thus called the Modal Ontological Argument (MOA). Modal logic is an extension of philosophical logic to deal with possibility and necessity. God is defined as a Maximally Great Being (MGB) and one key property of God is that He exists necessarily. The argument does not rely on concepts in the mind and seems to avoid all of Kant’s objections. The MOA is as follows:

- Premise 1: It is possible that God exists.

- Premise 2: If it is possible that God exists, then God exists in some possible worlds.

- Premise 3: If God exists in some possible worlds, then God exists in all possible worlds.

- Premise 4: If God exists in all possible worlds, then God exists in the actual world.

- Premise 5: If God exists in the actual world, then God exists.

The MOA refers to possible worlds and the concept of possible worlds is a big part of modal logic. A possible world is any possible combination of state of affairs.

Most people are initially puzzled by premise 3 which states that “If an MGB exists in some possible world, then an MGB exists in every possible world”. Why is this so? One property of an MGB is that an MGB is a necessary being. Therefore a necessary being can exist in one possible world then he/she/it must exist in all possible worlds. The rest of the premises and the conclusion follow in a fairly natural way. Thus according to William Lane Craig only premise 1 is controversial (It is possible that an MGB exists).

However, what does “possible” mean? “Possible” means “metaphysically possible” rather than “epistemically possible” Does this sound confusing? Metaphysically possible means “is it actually logically possible?” whereas epistemically possible relates to our knowledge. For example, if I say “Gee, I dunno, therefore I guess it’s possible” that is not what the argument means by possible. Thus possibility is not an appeal to ignorance.

The argument is also not implying that existence is a property or predicate. Existence may not be a property but type of existence is. The type of existence may be

- Impossible (e.g. a square circle),

- Contingent (can exist in some possible worlds but not others, e.g. a unicorn), or

- Necessary (has to exist in all possible worlds, e.g. numbers, shape definitions or absolute truth)

7 Objections

Objections to the MOA usually come in 2 types. These are:

- Parodies, or

- Claims that a MGB is incoherent or impossible.

7.1 Parodies

Parodies are not really an argument. Parodies are attempts to use parallel arguments to prove the existence of things we don’t believe in and so demonstrate the absurdity of the original argument. If the parody is valid then there is further work to do. We still have to find the flaw in the original argument. What we think we find with the MOA is that all of the parodies contain flaws. The MOA only works for an MGB. We will look at some examples of parodies.

7.1.1 Necessarily Existent Pink Unicorn

Someone has attempted to use the MOA to prove the existence of a Necessarily Existent Pink Unicorn. The argument goes like this:

- It is possible that a Necessarily Existent Pink Unicorn (NEPU) exists

- If it is possible that a NEPU exists, then a NEPU exists in some possible world

- If a NEPU exists in some possible world, then a NEPU exists in every possible world

- If a NEPU exists in every possible world then a NEPU exists in the actual world

- Therefore a NEPU exists

However there are problems with this parody. The counter argument is as follows:

- A pink unicorn is physical

- All physical objects/beings are contingent

- Therefore a pink unicorn cannot be a necessary being

- Therefore premise 1 fails

7.1.2 Reverse OA

The reverse MOA is an attempt to use the same argument structure to prove that an MOA does not exist.

- It is possible that an MGB does not exist

- If it is possible that an MGB does not exist, then an MGB does not exist in some possible world

- If an MGB does not exist in some possible world, then an MGB does not exist in every possible world

- If an MGB does not exist in every possible world then an MGB does not exist in the actual world

- Therefore Maximal Greatness is impossible

However, Premise 1 is tantamount to saying that it is not possible that an MGB exists. Thus it assumes its conclusion and is begging the question. Likewise premise 2 is question begging.

7.1.3 Dawkins’ Ontological Argument

Richard Dawkins has proposed an OA to prove that God does not exist. The Argument is as follows:

- The creation of the world is the most marvellous achievement imaginable.

- The merit of an achievement is the product of (a) its intrinsic quality, and (b) the ability of its creator.

- The greater the disability (or handicap) of the creator, the more impressive the achievement.

- The most formidable handicap for a creator would be non-existence.

- Therefore if we suppose that the universe is the product of an existent creator we can conceive a greater being namely, one who created everything while not existing.

- An existing God therefore would not be a being greater than which a greater cannot be conceived because an even more formidable and incredible creator would be a God which did not exist.

- Therefore, God does not exist.

However, it is incoherent and impossible to propose creation by a God who does not exist.

7.2 Incoherency

As well as using parodies other people claim that the idea of an MGB is incoherent. These are versions that claim that it is not possible that an MGB exists. These are typified by:

- The Omnipotence Paradox, and

- The Problem of Evil

The omnipotence paradox is “Can God create a stone that is so heavy that he cannot lift it?” The idea is to show that one or more of God’s attributes are incoherent or self –contradictory. However, No-one claims that God can do the logically impossible, such as creating a square circle.

The other objection is that the presence of evil means it is impossible that an MGB exists. However, we deal with this issue in other sessions.

8 Essence of Argument

In conclusion, what is the essence of this argument? Is it just playing with words or does it have a core argument that is compelling. The core argument that really makes sense to me is that if it is possible that a Necessary Being (NB) exists then that NB must exist in all possible worlds. This makes sense and seems necessarily true.

Some have claimed that it is a good argument but it still does not convince people. However, William Lane Craig believes in the argument and has started using it in debates. Craig used the MOA in a debate with Victor Stenger. Stenger attempted to use a parody, which was a maximally great pizza. However, Craig easily demonstrated that a maximally great pizza is incoherent, since a really great pizza is meant to be eaten.

However, is the OA helpful in other ways? I believe it is. I have heard it claimed that it never convinces anyone. However, this is not always true. A student did his PhD on the MOA and eventually convinced his supervisor. The MOA also asserts that God is maximally great in every possible way. This may feed into the Moral Argument and be one solution to the Euthyphro Dilemma.

Kevin Rogers

On Thursday 23rd of May we held our first debate. I debated Laurie Eddie on the subject “Does God Exist?” It would be unfair for me to make any judgement on the result of the debate, as I may be a little biased. However, I believe everyone enjoyed themselves and found it interesting, including Laurie. It was our largest meeting so far.

The debate is on YouTube. See

You can access the slide presentations at The Case For the Existence of God and The Case Against the Existence of God.

Check it out and make up your own mind.

Kevin Rogers

Leibniz’s Cosmological Argument

The Principle of Sufficient Reason

By Kevin Rogers

1 Introduction

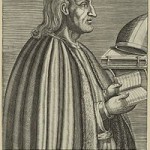

Why does anything at all exist? Why is there something rather than nothing? These were the questions that Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) raised, and from them he developed an argument for the existence of God based on the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR). The PSR is one form of various cosmological arguments.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716)

Leibniz was a German mathematician and philosopher. In mathematics, he was the co-inventor (with Isaac Newton) of calculus, the first inventor of a mechanical calculator and the inventor of the binary number system. In philosophy, he suggested that we live in the “best of all possible worlds”, he was a key thinker in the development of rationalism and also a forerunner of modern logic and analytic philosophy. In his latter years, he fell out of favour due to disputes with Newton on whether he had copied Newton’s ideas on calculus. His writings were largely forgotten, but were revived in the 20th century, and he is now highly regarded.

2 The Argument

Leibniz’s argument consists of 3 premises and 2 conclusions, as follows:

- Premise 1: Everything that exists has an explanation of its existence

- Premise 2: If the universe has an explanation of its existence, that explanation is God

- Premise 3: The universe exists

- Conclusion 1: The universe has an explanation of its existence

- Conclusion 2: Therefore the explanation of the universe’s existence is God

However, is it a good argument? A good argument must satisfy the following criteria:

- The premises must be true, and

- The conclusions must follow logically from the premises.

In this article, I will work backwards. I will firstly discuss the logical structure of the argument (its validity) and then consider the premises. We will firstly assume that the premises are true and verify whether the conclusions follow from the premises.

3 Logical Structure

Conclusion 1 is justified by Premise 1 and 3 as follows:

- Premise 1: Everything that exists has an explanation of its existence

- Premise 3: The universe exists

- Conclusion 1: The universe has an explanation of its existence

Thus if everything that exists has an explanation of its existence and the universe exists, then it follows that the universe has an explanation of its existence.

Conclusion 2 follows from premise 2 and conclusion 1 as follows:

- Premises 2: If the universe has an explanation of its existence, that explanation is God

- Conclusion 1: The universe has an explanation of its existence

- Conclusion 2: Therefore the explanation of the universe’s existence is God

I think it is fairly self-evident that the logical structure of the argument is valid. Now we will look at the premises.

4 Are the Premises True?

4.1 Premise 3

Premise 3 states that the universe exists. I think this is fairly self-evident. I am sure that there have been extreme sceptics that have questioned this claim, but I will not concern myself with them.

4.2 Premise 1

4.2.1 Objection 1 – How do we explain God?

Premise 1 states that everything that exists has an explanation of its existence. This has prompted the following objection:

If premise 1 is true, then God must have an explanation of his existence. The explanation of God’s existence must be some other being greater than God. That’s impossible; therefore, premise 1 must be false.

However, this objection is a misunderstanding of what Leibniz meant by “explanation”. According to Leibniz, there are 2 kinds of explanations:

- Beings that exist necessarily (necessary beings), or

- Beings that are produced by an external cause (contingent beings).

Necessary beings are those that exist by a necessity of their own nature. In other words it is impossible for them not to exist. Some mathematicians believe that abstract mathematical objects, such as numbers, sets and shapes (e.g. circles and triangles) exist necessarily. Necessary beings are not caused to exist by an external entity and necessarily exist in all possible worlds.

On the other hand, contingent beings are caused to exist by something else. They do not exist necessarily and exist because something else produced them. This includes physical objects such as people, planets and galaxies. It is easy to imagine possible worlds in which these objects do not exist. Thus we could expand premise 1 as follows:

Premise 1: Everything that exists has an explanation of its existence, either due to the necessity of its own nature or due to an external cause.

It is impossible for God to have a cause. Thus Leibniz’s argument is really for a God who must be a necessary, uncaused being. Thus the argument helps to define and constrain what we mean by “God”.

4.2.2 Objection 2 – Does the Universe need explaining?

Some atheists have objected that premise 1 is true of everything in the universe, but not the universe itself. However, it is arbitrary to claim that the universe is an exception. After all, even Leibniz did not exclude God from premise 1.

4.2.3 Objection 3 – An Explanation of the Universe is Impossible

Some atheists have suggested that it is impossible for the universe to have an explanation of its existence. Their argument goes something like this:

The explanation of the universe would have to be a prior state of affairs in which the universe did not exist. This would be nothingness. Nothingness cannot cause anything, Therefore the universe exists inexplicably.

This objection assumes that the universe includes everything and that there is nothing outside the universe, including God. The objection has excluded the possibility of God by definition. However, an alternative definition is that the universe contains all physical things, but that God exists apart from the universe. This objection assumes that atheism is true and argues in a circle. It is clearly begging the question.

4.3 Premise 2

Premise 2 states that if the universe has an explanation of its existence, then that explanation is God. This appears controversial at first, but in fact it is not. This is because atheists typically argue that if atheism is true, then the universe has no explanation of its existence. Thus if there is an explanation of the universe, then atheism must be false (i.e., God is the explanation of the universe). This conclusion follows from the following rule of logic: If p => (implies) Q, then “not Q” => “not P”. An example is, “If it is raining, then there are clouds. Thus if there are no clouds, then it is not raining.”

One may object at this point that the word “explanation” is ambiguous. An explanation for something may be due to either an intelligent agent or a mindless, unintelligent prior event or cause. For example, suppose we have a rusty car. The existence of the car was due to intelligent agents, but the rusty degradation was due to mindless, unintelligent causes. If the ultimate explanation of the universe is mindless and unintelligent, then the argument does not take us very far. However, could the existence of the universe be ultimately due to mindless causes?

However, I don’t think that the LCA necessarily demands that the observable universe has an intelligent explanation of its existence. For example, suppose that this universe was birthed by some other universe. Well, that other universe would be the explanation of its existence. Of course, that would simply push the problem back one step further. Even if an atheist wants to appeal to an infinite past succession of universes, we can still ask of that infinite succession, “Why does it exist, rather than nothing and what is its explanation?” But at that point, what kind of explanation can there be other than some transcendent, necessary cause? So a rational atheist is forced to either concede the argument or claim that the cosmos exists inexplicably (without explanation).

4.4 Objection 4 – The Universe exists Necessarily

All atheistic alternatives now seem to be closed, but not quite. Some atheists have claimed that the universe exists necessarily (i.e., the universe is a necessary being). If that were the case, then the universe would not require an external cause. However, this proposal is generally not taken seriously for the following reason. None of the universe’s components seem to exist necessarily. They could all fail to exist. Other material configurations are possible, the elementary particles could have been different and the physical laws could have been different as well. Thus the universe cannot exist necessarily.

However, is it valid to resort to God as the explanation of the universe? Are there other possibilities? The universe consists of space, time, matter and energy. The cause of the universe must be something other than the universe. Thus the cause of the universe must be non-physical, immaterial and beyond space and time. Abstract objects are not possible candidates as they have no causal relationships. Thus it seems reasonable to conclude that the cause of the universe must be a transcendent, unembodied mind.

5 Conclusion

Leibniz’s argument from the Principle of sufficient reason is an interesting argument for the existence of God, but it goes beyond just God’s existence. It also constrains the attributes of God to be a transcendent, uncaused, unembodied mind, who necessarily exists. In other words, this being is what the major monotheistic religions traditionally refer to as “God”.

1 Introduction

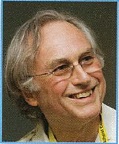

I attended the Global Atheists’ Convention held at the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre from Friday 13th April (good luck?) to Sunday 15th April. Our GPS did not recognize “1 Convention Place” and so we had difficulty finding where to go. Ann dropped me off where we thought it was. Almost as soon as I got out of the car, none other than Richard Dawkins walked straight past me; so I knew I was in the right place.

Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins is one of the “Four Horseman of the Apocalypse”. “The Four Horsemen” is a play on the corresponding figures in the Book of Revelation (chapter 6). The 4 horsemen are outspoken figures for the new atheism movement. The other 3 are Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris and Daniel Dennett. Unfortunately, Christopher Hitchens died of cancer on December 15 last year and so he declined to attend. However the other 3 were there. Their key books are shown in the following table.

Table 1: Key books by New Atheists

| Author |

Book |

| Richard Dawkins |

The God Delusion |

| Christopher Hitchens |

God is not Great